- Webnote 16: Highlights from 1993 Extraordinary meeting and EGM

- Webnote 17: Note on Exxon Valdez lawsuit

- Webnote 18: Lloyd’s corporate members for 1994

- Webnote 19: Further Notes on Stephen Merrett

- Webnote 20: Hardship Assistance

- Webnote 21: Further Notes on Robert Hiscox at Lloyds

- Webnote 22: Letter from Robert Hiscox, 7 July 1993

- Webnote 23: Initial Equitas project structure

- Webnote 24: Gooda Walker Action Group (GWAG)

- Webnote 25: Lloyd’s First Settlement Offer, December 1993

- Webnote 26: Raising Standards, Changing Values

- Webnote 27: Terms of Reference and Membership of Value Group

Webnote 16: Highlights from 1993 Extraordinary meeting and EGM *

1993 Extraordinary Meeting

As the book describes, a large meeting was held in the Albert Hall in May – partly to explain the Business Plan to Names, announce the initiatives to try to work towards a settlement, and take questions. This was Rowland’s first big encounter with thousands of members. The work of the two panels announced by Middleton at this meeting was eventually to form the basis of a central settlement offer made in December 1993 to all Lloyd’s members. Relevant highlights are in the book.

1993 EGM

In June – briefed about Lloyd’s intentions – both Neil Shaw and Christopher Stockwell called for a change in the byelaw surrounding EGMs. Shaw thought it “ludicrous that Lloyd’s, with a current membership of over 20,000 can be forced to suffer the disruption and cost of an EGM at the request of no more than 100 members.” Stockwell described the situation as farcical. Shaw said that a quoted company would require members with 10% of its shares to make a similar request. Lloyd’s moved swiftly by passing a byelaw raising the threshold to 1,500 members. This was not retrospective and did not affect the meeting already called by Gurney’s supporters and now fixed for July 5. Richard Astor’s response was scathing: “Lloyd’s can run but not hide. This pathetic attempt to compare itself with company procedures will rebound.” Astor, a member, revealed that he was organising legal action against at least two former Chairmen and said he planned to put the corporation into liquidation. (Financial Times June 11 1993.)

The second EGM went ahead. Once again, Lloyd’s turned to the ALM for help in expressing the more moderate, mainstream point of view to counter the resolutions. Gurney promised not to give up until justice was done. He said some good changes had taken place but “mostly our hopes have been raised falsely, alas only to be dashed.” He complained that things were now less clear-cut. Last year, however unpalatable, Names had known where they stood: they were characterised as whingeing and bitching, while underwriters were allowed unfettered discretion. Sympathy and crocodile tears had been the order of the day. Now, he said, the leadership shouted their guilt from the rooftops, almost proudly. “So we can quote from the Chairman and Chief Executive and say that there has been mismanagement, deception, incompetence, lack of professionalism, mis-regulation, yes this and more.”

He praised Middleton and suggested that he should be given a chance to lead from in front rather than behind. Rowland and Merrett should get off his back. Rowland had been on the Council when the dreadful losses were passing through the market. His firm had made money broking LMX business. The most charitable thing that could be said about him was that he was a good man who stood idly by whilst evil triumphed. He made a personal attack on Garraway’s ill health which drew a sharp rebuke from Rowland. He described the ALM as the Council’s poodle.

Resolution 1: Lloyd’s itself, its staff and Council members:

* owe fiduciary duties of care to members

* are not exempt from having to pay damages to any person

In proposing the first resolution, Philip Dinkle cited Miller’s AGM speech in 1984, describing the duties of Council. He gave his own account of the last ten years, which he saw as a cover-up of the huge liabilities, and false market. Parliament had been fooled into granting Lloyd’s immunity so that the Council could act fearlessly. But they had not done so. He said Lloyd’s had a duty of care to Names and it was an obscenity to say otherwise. The authorities at Lloyd’s had fought tooth and nail against acknowledging their duties. Peter Nutting described the resolution as at best naive and at worst motivated by malice. He pointed out that all regulatory bodies appointed under the Financial Services Act and their employees had a similar immunity. They could not do their job without it. The resolution was ridiculous, unhelpful and misconceived.

Resolution 2: We welcome corporate capital subject to:

* Lloyd’s disseminating a prospectus indicating how members will be fully compensated thereby for the goodwill and assets of the Corporation, which belong to members at 1/1/93 and for the regulatory failures highlighted in the Business Plan, and

* the subsequent approval of this prospectus by two-thirds of members in a postal ballot

Daniel Salbstein spoke for the second resolution which supported proposals in a document entitled Lloyd’s, An Improved Solution, produced by a Canadian Name called David Springbett. He recited his own version of Lloyd’s recent history. This was that since the 1871 Act created the Committee with a statutory obligation to advance and protect the interests of members, bit by bit, the interests of the agents had been advanced to the detriment of the Names. Later the agents were allowed to be incorporated and fattened up for sale. The 1969 Cromer report had been circulated only to senior directors of the agencies and concealed from the Names for 17 years. This had given the green light to the share sellers. The Committee favoured the insiders’ interests at the expense of the Names; that was when the rot really began. Cromer’s committee had included some distinguished individuals who said there was an urgent need for reserves and a tax-sympathetic approach, especially because of Lloyd’s North American catastrophe business. He thought the tax concessions finally won when “Lloyd’s was on its deathbed” could have been secured in 1969.

Salbstein recalled the history of the deficit clause first proposed by Cromer but avoided and delayed by an agent-dominated Committee for two decades. The immunity had been intended to allow Lloyd’s to energetically regulate the market. But this was precisely what it had failed to do. Salbstein finished by telling Rowland that he admired his smoothness and compared him with Lenin. At first he had been with the peasants [in this case the Names] and then turned against the peasants. Rowland would do the same. The victims would be “screwed in the ring fence.” He urged Rowland to put his weight behind an improved solution for Lloyd’s, so that his reputation could be vouchsafed for posterity.

Neil Shaw spoke to his resolution, which supported the Council and Business Plan. He declared that he was not a poodle and nor was the ALM. Sarcasm was not their tool. On a postal ballot, 68% and 69% respectively had voted against the hostile Resolutions 1 and 2. The supportive Resolution 3, put forward by the ALM, received the backing of 77% of the voters on a 60% turnout. Rowland said this support gave Lloyd’s a clear mandate to implement the Business Plan and return Lloyd’s to profit.

Webnote 17: Note on Exxon Valdez lawsuit *

The lawsuit mentioned in the book was filed in a federal court in New York in August 1993. It followed a suit filed by the oil company against the insurers in Texas in early August, in which the insurers sought to establish that they were not liable for payment of certain claims made by Exxon. The underwriters believed that the New York federal court was the proper forum for arbitration and any litigation, as defined in the relevant insurance policies. Underwriters had denied that some of the claims presented by Exxon, as the owner of the Exxon Valdez cargo, were covered under certain global corporate excess insurance agreements. Underwriters said there was no cover because the excess policies specifically excluded claims and spills from specified Exxon tanker ships, including the Exxon Valdez. Such claims were separately insured.

The insurers, led by Lloyd’s underwriter Richard Youell, also alleged that the Exxon Valdez was un-seaworthy, that Exxon knew this, and that was the cause of the stranding in Prince William Sound. The insurers also contended that Exxon failed to act as a prudent insured party by not vigorously defending itself against the imposition of liability: both as a marine cargo owner and by failing to pursue potential claims for indemnity against third parties.

The lawsuit also cited the allegations of criminal indictment brought by the US government against Exxon and civil actions in Alaska which argued that Exxon’s intentional misconduct caused the pollution incident. Underwriters contended the stranding and resulting pollution occurred as a result of Exxon’s “wilful, wanton, reckless and/or intentional misconduct.” Exxon argued that its insurers had failed to act in good faith over its claims and was suing the insurers for breach of contract, seeking to make them severally liable for damages to cover all its claims. The insurers denied all allegations of bad faith and argued that Exxon failed to fully cooperate by withholding relevant documents.

Much more material is available on the internet about this unusual and controversial case.

Webnote 18: Lloyd’s corporate members for 1994 *

| Quoted Investment Trusts | Capital Raised |

| London Insurance market InvestmentTrust Limited (LIMIT) | £280m |

| CLM Insurance Fund | £ 86m |

| Angerstein Underwriting Trust | £ 67m |

| HCG Lloyd’s Investment Trust | £ 65m |

| New London Capital Plc | £ 60m |

| Delian Lloyd’s Investment Trust | £ 51m |

| Masthead Insurance Underwriting | £ 40m |

| Premium Underwriting Plc | £ 33m |

| Syndicate Capital Trust | £ 32m |

| Finsbury Underwriting Investment Trust Plc | £ 30m |

| Abstrust Lloyd’s Insurance Trust | £ 30m |

| Hiscox Select Insurance Fund | £ 30m |

| Other Vehicles | |

| Lomond (formerly Murray Underwriting Ltd) | £ 27m |

| Navigators Corporate Underwriters Ltd | £ 19.25m |

| Camperdown Corporation (St Pauls) | £ 14m |

| Hiscox Dedicated Corporate Member Ltd | £ 10m |

| Absa Syndicate Investment | £ 6.5m |

| Wentworth Underwriting | £ 5 m |

| Kiln Cotesworth Corporate Member Ltd | £ 2.25m |

| Yasuda Lloyd’s Corporate Member Ltd | £ 1.5m |

| MICAL | £ 1.5m |

nb: Four further corporate members, providing £13m of capital in aggregate, were not named in this article which appeared in the January 1994 edition of OLS.

Webnote 19: Further Notes on Stephen Merrett *

…and his career at Lloyd’s

Stephen Merrett was the young underwriter to whom the Chairman had turned for help with the troubled Sasse syndicate, described at Webnote 10. His assiduous probe revealed the dimensions of that problem. Several years later, he was described by the Times as the underwriter who had masterminded the market rescue for Sasse Names hit by fraud.

As well as building his own syndicate to be the largest at Lloyd’s, he acquired various companies in order to strengthen his agency, and to take Lloyd’s into the UK provinces and the retail market for insurance. In 1987 he was heading towards a stock exchange listing for the group. In January 1988, the Evening Standard reported views that his agency could be worth between £100 – 150 million.

He was once reported as having donated a large sum to his Oxford College, stipulating that no building should be named after him or his company.

He was a member of the Committee of Lloyd’s from 1981 and later the Council, until 1984. When Sir Peter Green stepped down as Chairman in 1983, there was some speculation that Stephen Merrett, among others, might be his successor. In the event, Peter Miller became the next Chairman. When the Chief Executive, Ian Hay Davison left in 1985, there was even a rather uninformed suggestion that ‘the ubiquitous’ Merrett might take over that role.

He was a widely respected underwriter, with a reputation for not suffering fools gladly. His role as a leading errors and omissions underwriter conferred a good deal of effective power in his hands. At one stage he wisely declined to provide errors and omissions cover to Feltrim, a managing agency, frankly saying that he doubted their competence. He was proved right when the Feltrim agency subsequently lost a spectacular amount and was judged negligent.

In 1985, Merrett was critical of the sentences imposed by the Lloyd’s disciplinary tribunal’s on Peter Cameron Webb and Peter Dixon, referring to the lengthy delays and in some cases the ‘extraordinary levity’ of the sentences in view of the seriousness of the crimes. He called for an early settlement of the PCW issue, described in Note 10. He chaired a group that supervised Lloyd’s negotiations with the Revenue, participating in meetings that explored the nature of RITC with both the Revenue and the US Treasury.

He and David Rowland topped the poll among working Names in 1986 and were elected to the Council for a four year term – his second term, Rowland’s first. Among extra duties, he became Chairman of the important Solvency and Security Committee and took a close interest in the impact on the Lloyd’s market of US pollution claims. In 1992 he was made a member of the Superfund Commission in the US, described in Webnote 36.

Merrett routinely applied his underwriter’s attention to detail to Council and Committee minutes and papers. A stickler for accuracy, many a meeting began with his corrections to the minutes. At Council he was notably respectful of the position of external and nominated members.

He was chairman of the Lloyd’s [Marine] Underwriters Association (LUA) for 1991 and 1992. When David Rowland came to form the task force, Merrett, as Lloyd’s most obvious heavyweight thinking underwriter, was a natural choice to join it. He contributed a great deal to its deliberations, notably to the issue about how to approach the massive problem of Lloyd’s inheritance of US liability claims. He was a strong proponent of combining and strengthening Lloyd’s expertise in this field to create a ‘centre of excellence.’ He was among those who proposed the creation of what became Equitas.

In July 1992, there was much speculation that Coleridge was on the point of standing down as Chairman of Lloyd’s. Press rumours about his successor centred on two Names: Rowland and Merrett. There were several reports that underwriters greeted the prospect of being led by a broker with some disquiet. Merrett was said to be the underwriters’ choice. He did not declare his candidacy, nor did he rule it out. Once again, he and David Rowland stood for election to the Council for the following year. Both were elected, with Merrett a close second in terms of votes.

But even in the heady days of new leadership, the choice of Merrett as Deputy was controversial in some quarters, not least with his fellow-Deputy Hiscox, who scented trouble. This was because some Merrett syndicates had brought big losses to Names, leading to disputes. The source of losses for US asbestos and pollution liabilities are discussed in the book. The sequence of events surrounding disputes with Names is briefly outlined below; the full story is very complex.

In 1988, Merrett had left ‘open’ the 1985 year of account for his major syndicate 418, because of uncertainties about the eventual cost of claims arising from eleven run-off policies it had underwritten for other syndicates. This meant that, like Outhwaite, though on a considerably smaller scale, Merrett faced a significant share of the rising estimates for the eventual cost of settling US liabilities – both asbestosis and pollution. The extent of liability for some of these run-off policies was contested, becoming subject to arbitration.

Leaving the year open was the response demanded by members’ agents to the scale of uncertainty about their eventual cost. Syndicate 418 also declared a loss caused by the need to strengthen its reserves to meet these old claims. Soon after that it was reported that plans to list Merrett Holdings on the Stock Exchange had been shelved for the time being. Within a month of Merrett’s decision to leave the 1985 account open, angry Outhwaite Names met in the Baltic Exchange to discuss legal action over their large losses. It took several years for Merrett’s own Names to follow the same course.

In 1990 Merrett Holdings made pre-tax profits of £9.9 million. Stephen Merrett said these profits were the best ever achieved by the group and reflect their participation, through profit commission earnings, in the syndicate results of Lloyd’s 1986 year of account. Profit commission would have been £2.4 million higher still, had not Merrett waived commission on its large marine syndicate 418 for Names who were on the syndicate in 1985. He hoped that disputes with reinsured syndicates would soon be settled, allowing 418 to close its 1985 account the following year. Plans to seek a stock market listing could then be revived.

In February 1990, Lloyd’s List reported “reinsurers have made their first major breakthrough in the round of disputes over unlimited run-off policies. The key arbitration has upheld the right of leading underwriter Stephen Merrett to avoid liability for the heavy US asbestos and pollution claims… This will mean more than 500 Names on Pulbrook could face a cash call of up to $50 million for the 1985 underwriting year.” Names on the Pulbrook syndicate became very restive. The Merrett agency had acquired Pulbrook from Stewart Wrightson in 1985. Pulbrook was itself reinsured by the large Merrett syndicate 418, which successfully disputed the reinsurance: this arbitration declared it void on grounds of nondisclosure of material facts. Angry Pulbrook Names accused Stephen Merrett of a conflict of interest, but he said he had kept his distance from the issue. They formed an action group, led by Clive Francis, a former RAF pilot who had made money in property.

In early November 1991, it was reported that 200 members of Merrett’s syndicate 418 met at Chelsea Town Hall to discuss allegations that the syndicate had unfairly recruited Names in the 1980s to spread the burden of its asbestos and pollution losses. They faced an average loss of £16,000, which was expected to rise as more claims emerged. Ken Lavery, a Canadian Name had organised the meeting. He alleged that the 2,000 Names who joined syndicate 418 in 1983, 1984 and 1985 were deceived by earlier annual reports saying the syndicates’ reserves were adequate. He also lodged a complaint against the auditors, Ernst and Whinney.

More than two thirds of the Names at the meeting backed a motion calling for the appointment of Richards Butler, a City law firm, to seek leading counsel’s opinion on whether they had a basis for a legal claim. In late November 1991, The Sunday Times Prufrock column said “The bigger they are, the harder they fall. The fortunes of Stephen Merrett, the star underwriter at Lloyd’s of London, seem to be waning on all sides. Already on the receiving end of US legal action and a mass protest from his British members, he now faces a decline in business capacity for next year.”

As reported in Chapter 3 of the book, when the court case against Outhwaite seemed poised to conclude that he had been negligent, a settlement was negotiated between Peter Nutting on behalf of the Outhwaite Names and Stephen Merrett, on behalf of the errors and omissions underwriters – the main target of the litigation.

Within days of the Outhwaite settlement, it was reported that Stephen Merrett had come under attack from some of his own Names, who had formed an action group, reported to be led at that early stage by Clive Francis. Their next step was to appoint accountants and solicitors to investigate whether Names on Merrett’s flagship syndicate 418 had a claim. Francis said: “After the Outhwaite case, the mood of members has changed as they have shown they can beat the system.”

Early in December 1992, around 600 of the Names on syndicate 418 met at the Royal Geographical Society’s hall in London’s Kensington. A vote in favour of proceeding with litigation was announced soon afterwards. They were advised by Anthony Boswood QC, who had led the successful action against Outhwaite. He said that Names who joined syndicate 418 in 1984 and 1985 had a strong claim arising from the decision to close the syndicate’s 1983 and 1984 years. They could claim against both the managing agency and the auditors who he thought had acted in breach of their duty of care to the Names, by allowing these years to be closed. As with the Outhwaite case, members’ agents could be held accountable; their errors and omissions insurance was the main target. Names on earlier years were in a different position, although Boswood believed they could also take action alleging negligence in respect of underwriting the run-off contracts.

In May 1993, Business Insurance, a trade journal, reported that Stephen Merrett, the senior Lloyd’s underwriter who spearheaded a solution to Lloyd’s open year problems in the market’s new business plan, was leaving open the 1990 underwriting year of syndicate 418. Soon after this, Merrett announced his decision to stand down as the active underwriter for the syndicate. He was expected to spend more time on developing group activities and especially with attracting incorporated capital.

At the end of July 1993, the Merrett agency, advised by lawyers who were instructed by their own providers of errors and omissions insurance, criticised the Lloyd’s loss review into syndicate 421, which was managed by the Merrett group. Losses had reached 700%. In a nine-page letter to its members, the agency said that the loss review committee’s comments “appeared ill considered, suggesting it had failed to research and address several key topics.” Among other things, the agency thought the report’s treatment of asbestos and pollution claims was ‘inadequate and unbalanced.’ In early August, the FT reported an un-named senior figure as saying “it is fine for Stephen as an underwriter to criticise the report. But he can’t do it and be Deputy Chairman… This is a pretty widespread feeling in the market.”

Merrett disagreed with this, saying it was quite proper for him to make criticisms in his capacity as a managing agent without interfering with his responsibilities as Deputy Chairman. He stressed that he was ‘entirely in support of loss reviews so that Names get information on major losses.’ Soon afterwards, the Association of Lloyd’s Members (ALM) expressed a view that he should step down. More difficulties followed when Merrett met with members’ agents later in August in an attempt to shore up support for his syndicates. Soon he was even offering to stand down as agency chairman if that would help stem the loss of support.

On September 9 1993, The Independent reported, a little triumphantly, “a new crisis hit Lloyd’s yesterday as Stephen Merrett, Deputy Chairman of the troubled insurance market, resigned from his post and stepped down from the ruling Council. It is the first time in recent memory a top figure on Lloyd’s ruling body has resigned from it midway during a term of office.” The newspaper went on to quote from an exchange of letters between Rowland and Merrett. Referring to his very substantial workload, Merrett asked Rowland to accept his immediate resignation from the Council. Rowland said his contribution would be missed, and his assistance would still be sought on matters affecting the market.

A bad year got worse for Merrett as he struggled to secure capital. He nearly struck a deal with the US Travelers insurance company, with support from Marsh, the largest broker at Lloyd’s, but this fell through at a late stage. The group announced talks with another Lloyd’s agency, the Archer Group, but these were quickly brought to an end. Even the group’s more obviously viable syndicates were threatened with run-off. Able executives and underwriters took up offers in greener pastures. The better syndicates were sold to several agents, while the old flagship 418 went into run-off.

Later in the year, Middleton convened a meeting to try to shore up some support for Merrett’s syndicates. One senior underwriter cleared his throat and said he would say what others were thinking: they did not want to help. The market that had elected him as Chairman of his underwriting association, and three times to its governing body, was now taking a very different line. With falling capacity, many market players were content to see the inevitable contraction falling on someone else. “Lloyd’s friendships are fickle” Merrett said 20 years later. 1993 had begun with Merrett freshly elected and made Deputy Chairman. It ended with the loss of office and the collapse of his business. Worse was to come when his Names had their day in court.

Webnote 20: Hardship Assistance *

In an OLS interview in April 1994, Dr Mary Archer expressed confidence that the Lloyd’s hardship route offered members a more attractive package than bankruptcy. It featured the same three-year recovery time for payments out of income and windfalls as UK bankruptcy, but much more generous treatment of the home and even income support in some cases.

Archer said she regarded equity of treatment as paramount and that any improvements made to the scheme were applied retrospectively as well as prospectively. The aim was always to protect the member’s home, provided this was no more than modest. Where the member’s funds at Lloyd’s were in the form of a bank guarantee secured on his home – as they were in about half the then current hardship cases – Lloyd’s seldom drew down on the guarantee if this exposed the Name to the risk of dispossession. Instead it was released, with Lloyd’s taking a charge on the property that would not be enforced until after the deaths of the member and spouse. Also, if the member’s income was insufficient to meet the reasonable domestic needs of himself and his family, Lloyd’s offered income support by putting some of his capital into a trust fund which paid income to him for his lifetime, returning the capital to Lloyd’s on death. This was more generous than bankruptcy where there would be no possibility of making income payments out of capital seized by a trustee in bankruptcy. Individual Voluntary Arrangements (IVAs) were more suitable where the Name owed money to other creditors. Unlike bankruptcy and IVAs, which were made public, hardship arrangements were private.

Archer explained that Lloyd’s never attacked assets that had always belonged to the spouse, except where they had been used to support the Name’s underwriting. But Lloyd’s did ask for the spouse’s financial position to be disclosed, so they could consider making a hardship trust fund, and to be satisfied the Name had not recently transferred assets to his spouse improperly. She explained that the hardship agreement detailed the payments to be made and the other steps the Name needed to take, but beyond that, their financial affairs remained entirely in their own hands. It was a myth that Lloyd’s wanted to take over their financial affairs. By contrast this is what happened in a bankruptcy.

Payments sought from the Name’s income depended on the income and expenditure of the family as a whole. Where the income fell above the guideline figure, taking into account all the family circumstances, periodic payments from income were requested for a three year period only. The current income guidelines were £17,600 for a member and his or her spouse and £11,600 for a single member, with additional allowances for taxation, national insurance and mortgage payments. “Below that income level we do not ask any payments out of income; we may offer income support by putting some or all of what used to be the member’s capital into a hardship trust fund to pay him income. However we can only restructure members’ existing assets to generate income; there is no ‘pot of money’ to provide this, although I continue to press the case within Lloyd’s for a support fund.” At the time of this interview Lloyd’s had received about 1500 declarations and made proposals to about half of them. Names usually took some time to consider these proposals and then the hardship committee had about 300 acceptances, but only 30 signed legal agreements.

Once an application was established, the agent would stop drawdowns on the member’s deposit while the application was being considered. On applying, the member had to confirm that he was willing but unable to meet his underwriting liabilities; that he had resigned from active underwriting; declare his financial position; and agree to provide details of his spouse’s income and assets. From this point a case officer would guide them through the hardship process. Although many applications were dealt with through correspondence and over the telephone, case officers were willing meet members in their own homes or in Lloyd’s offices. Members were encouraged to come forward before it was too late. For example, if a member had cash at the bank and a low income, monies could be put into a trust to provide the member with an income for life.

One case officer said: “The most important thing is fairness. One person shouldn’t get a better proposal from the MHC that another, but some members are more vulnerable. You have to tailor each proposal to the member and their own circumstances.” For example, although the requirements were for the member to retain only a ‘modest’ property, those who were elderly or unwell might be allowed to retain their original residence on the grounds that the upheaval involved in moving could be unreasonable. Each case officer typically handled between 60 and 70 cases at any one time “You have to be very well-organised to do this job” said one. His personal aim was “to get the best deal for the Name, but to keep fairness for other Names.”

Spouses of members could also apply for hardship. These cases required the most time and patience. Widows of former members had very little understanding of Lloyd’s and were completely bewildered at the situation in which they found themselves. Handling these cases could be satisfying: “If you start with a case, especially the older ladies, where they think it’s a PR exercise and that nobody can help, and that they’re going to lose their house, and take them through on a handholding exercise, you can feel the increasing relief in their telephone calls and it’s very rewarding. It removes the fright of the postman coming up the garden path carrying yet more demands for money they don’t have.”

Each case officer began work with a mentor. It was difficult for the handlers not to become overly involved in individual cases. “We have to take a step back, sit back and listen” said one. “We have to take in the member’s feelings of anger and distress. But as people get it out of their system they start to come down and we can gradually switch to a more constructive conversation. Not everyone could be a case officer because it’s a very stressful and consuming job. You can’t help but have sympathy for people – and a lot of respect for them – but you must keep your distance.”

A common problem was members who had taken out large loans that they could not afford in order to meet their losses. A case officer explained.” This is a mistake. If they are facing such a problem they should come to us first and at least we can advise them on whether they are able to apply for hardship. We are here to do our best for our members.”

Webnote 21: Further Notes on Robert Hiscox at Lloyds *

During the 1960s, Robert Hiscox had recognised the difficulty of leading a business and contributing to the running of Lloyd’s through its Committee. He had seen this at first hand when his father, Ralph, was Chairman of Lloyd’s in 1967 and 1968. He lost money for five consecutive years and was close to going out of business because of his Lloyd’s roles, as Chairman, and other active roles in market associations, and committees such as Cromer. Robert Hiscox made a commitment to his Names each year not to stand for office within Lloyd’s while he built his firm. He thought that running profitable syndicates was better for Lloyd’s than sitting on committees. By contrast his fellow Deputy Chairman, Stephen Merrett, did try to combine these roles; some of his colleagues felt that Merrett became deflected from running his business. (Other elected Council members managed to do both, usually by being much less involved than he was: Merrett read all the papers carefully and took the lead on several complex subjects.)

By late 1992, Hiscox felt differently about getting involved in Lloyd’s affairs. Through his task force membership he had become acutely aware of the fragility of Lloyd’s, on which his business depended; his conviction that the whole structure was anachronistic had been reinforced. He had worked with outside advisers under Rowland’s task force chairmanship. He saw both a need to help save Lloyd’s and an opportunity to drive through some of the changes in which he had long believed. He wrote to Coleridge, then Chairman, in February 1992 offering to help. Hiscox suggested that Coleridge should share out the task of handling Lloyd’s PR to a wider group, including managing agents and brokers. He said the whole market was submerged beneath and dependent upon his persona, which was a pity. Coleridge agreed that others should become spokesmen too.

In 1993, when Hiscox was busy with Lloyd’s matters, he persuaded Bronek Masojada, originally part of the McKinsey team that had worked with the task force, to join him as a young and capable future managing director. Their close partnership lasted for twenty years until Hiscox retired. Looking back, Hiscox has mixed feelings about the time he spent as Deputy Chairman of Lloyd’s. At times he found Rowland’s leadership inspiring; at other times he would have liked more of a fighting general and less of a diplomat. He had the opportunity he wanted to introduce corporate membership and thereby transform the capital base of Lloyd’s and that of his own business. He is widely considered to have done this well, picking up the reins from earlier half-hearted efforts. He found himself working harder and harder. Like others, he was less available for his family than he felt he should have been. He contracted an illness towards the end of his three years which he partly blames on stress. But he looks back on the period as one of his biggest achievements.

Hiscox is a patron of the arts. He is a trustee of several foundations. He displays fine modern pictures and sculptures at home and at his office. For years the ground floor of his offices contained the Hiscox Arts Cafe, scene of many excellent exhibitions. During his time as an underwriter, he established a leading position in the insurance of art.

There were some consistent themes in Hiscox’ letters – ‘rants,’ as he calls them – to the Chairmen. He frequently said that the Council should have the power to exclude or discipline anyone that offended, and should have the courage to use the powers selectively rather than try to build an elaborate framework of rules and regulations to stop every potential abuse that they could conceive might happen. “We are in business and need entrepreneurial freedom – not a legal straitjacket created, in part, by those that have never worked in a marketplace.”

He was a self-appointed watchdog, always looking to promote the freedom of the market, high standards and to query nonsense. On one occasion, a Deputy Chairman’s market letter tried to justify a small increase in the annual subscription rate by referring to an offsetting reduction in central fund contributions. In doing so, it said that the central fund rate set for 1988 had “turned out to be too high.” Hiscox pounced: “I hate to be a bore but I assume that a simple mistake has been made which will be corrected shortly. However I have to ask what you mean when you say that the central fund contribution rate set in 1988 turned out to be too high. It is universally thought that the central fund is lamentably inadequate in today’s market, especially with about $1,000 million of un-reinsured retention from the Piper Alpha loss looking for somewhere to land. If you have not already sent out an amendment, I would be grateful if you could let me know what you meant.” (Letter from Hiscox to Coleridge 9/11/88).

In a letter to the Chief Executive in May 1985, Hiscox offered a general comment on the leadership, known then as ‘the second floor’: “Some members of the Committee of Lloyd’s seemed to forget that they are elected by members of Lloyd’s to represent them and serve their interests on the Council. They seem to behave as though they were chosen by some headmaster of Lloyd’s to discipline the market and keep it in order like school prefects. Too much respect is expected by members of the Committee and especially by the Chairs. Indeed, I have personally witnessed such deference shown by members of the Committee to the Chairs, even by a deputy chair to the Chair himself, that could only corrupt and cause a loss of a sense of reality.”

He spoke for many when he wrote to the Chairman in 1986 about privileges accorded to the Chairs “If they do not deliberately use the ordinary facilities available to all in the market, how can they ever remain aware of what is going on in the market and become aware of its needs and problems? The sight of a chauffeur driven car sweeping to the front entrance of Lloyd’s, of a waiter dashing forward to open the door, or the deputy chairman of Lloyd’s being escorted up the stairs with the waiter carrying his briefcase, or a lift being called to him to his exclusive use is all evidence of the ‘them and us’ attitude that so irritates the wealth creators in the market.”

Hiscox also chided the Chairman for not having brought a private prosecution against Peter Cameron Webb and others when the public prosecutor failed to do so. (The PCW scandal is described at note 10). He also challenged the lightness of the sentence against Sir Peter Green. He and others wanted to see much firmer treatment. One of Chairman Peter Miller’s replies to Hiscox said that if he believed that “we are all as big fools as you seem to imply, why don’t you get yourself elected to the Council and do something about it?”

Hiscox considers that standards of underwriting at Lloyd’s in the 1970s were often low. He had a law degree from Cambridge and watched some underwriters “issuing four over one ($4m excess $1m) ‘umbrella’ liability policies, covering every legal liability which could be incurred by a manufacturing business, in about 30 seconds, putting down a premium out of thin air, rather than by proper estimation of the likely eventual cost. These policies became absolute killers over time as they were held to cover asbestosis and pollution.”

Furthermore, unlimited expenses were provided for in the policies. “The minute I sat on the corner of a box in 1967, I stopped us from writing any liability business in America, because the wording included unlimited expenses and covered all losses occurring during the policy period, so that the loss could back on to that policy at any time in the future. Wholly unsuitable for an annual venture. I had read law so I enjoy reading agreements. My father always said that Sturge had done such a wonderful job and I said no they have not, they have written a lot of rubbish at the wrong rates, and we will live to pay for it.” (These remarks, and others cited below, were made during interviews with the author during 2012).

“I think that Kiln and ourselves were almost the only ones trying to apply some intellectual rigour to underwriting in Lloyd’s. Charles Skey was also an excellent underwriter. I tell our young people now that in the 1980’s we underwrote with no idea of our aggregate liability. Nowadays we have heat maps and immense detail of risk. It all comes in electronically; we have a good estimate of our aggregate liabilities everywhere.”

“One of the biggest idiocies was that if you reinsured with a Lloyd’s syndicate you got a dispensation on your premium income. All the pressure was therefore to do that, rather than be penalised by reinsuring outside with someone like the Munich Re. Lloyd’s thought that it was the e?lite and everyone else was ‘the fringe market’. They thought it would be safe because they were thinking subscription; they loved subscription. They didn’t realise you can pass risks around in a vicious circle, with a small risk spiralling round the market until underwriters ran out of reinsurance. So the governance was appalling; there wasn’t any to be truthful. There was nobody monitoring the underwriting. Syndicates made serious losses; their Names abandoned them, but were then left trapped in indefinite run-off. I remember a case where an underwriter died and the deputy became the underwriter. We mentioned we might take it on and he said ‘Oh, no, no I’ll give it a go for a while and see how it goes.’ If a syndicate went into run-off in those days, it was relatively painless as fairly soon some other syndicate would absorb the account. It wasn’t until asbestos came along that suddenly run-offs became agony for the trapped Names with perpetual losses rolling in with no time limit.”

Hiscox says “I hated unlimited liability. I got my first Name in the early 1970s. I went to stay with him. He was a rich guy in Yorkshire. I just shivered at the thought he had put everything at risk. He had some wonderful objects in the house and I thought this was all at risk to our underwriting. I just thought this is ridiculous.” In 1987 shortly after the budget which removed tax advantages for individual Names, Hiscox lost no time in writing to the Chairman and suggesting that this presented a ‘once-in-a-century opportunity’ to make a change in the status of the investor in Lloyd’s. This would be of enormous benefit to the future. With the loss of tax advantages, now was the time to get rid of unlimited liability. He said that he and a few others had been attracted to moving their underwriting businesses outside Lloyd’s where they could raise capital from companies or limited investors, free from the growing restrictions of the Lloyd’s system. Miller had replied saying that unlimited liability had been debated at Council, which had concluded it should continue. He also believed all the regulations introduced had been necessary.

As the book records (page 130), Hiscox believes the advent of corporate capital saved Lloyd’s. “In 1993 Names were running out the door. Capacity was heading down to £5 billion. Corporate capital came along, and the Names turned round like a cartoon mouse and come back in when they realised we had raised a billion.” Rowland and Hiscox were not immune to criticism by external members. Hiscox was sometimes characterised as an insider who was unsympathetic to the Names that had incurred big losses. Many Names associated him with a phrase he once quoted from the film The Magnificent Seven: “If God had not meant them to be sheared, he would not have made them sheep.” In the circumstances of heavy losses suffered by many Names this sounded utterly heartless; it was dragged out incessantly. In 1993 Hiscox issued a letter – reproduced as Note 22 below – pointing out that he used the quote in a quite different context, twelve years earlier in 1981, in a time of profits, referring to those Names who regularly put up with low returns instead of changing their agent or their syndicates. It was said in a private letter to John Rew, debating the merits of his league tables of syndicate results. Hiscox’ explanation is reproduced below for the reader to put it in context and reach his own conclusions.

Hiscox believes that he was the first to suggest that all old year claims should be brought together. He recalls: “I remember suggesting the Equitas plan, getting up and putting it on a display board at a meeting in the Hilton hotel. My plan was simply to get all the old years in Lloyd’s into one pot to save money. I was not thinking of liberating Names, which was second to the cost savings. I remember saying ‘all these syndicates, all these open years put them all in one pot’. Merrett got up and put in the Centre of Excellence which was already in existence to settle the old claims. (It wasn’t a new idea because I had actually been a founder of Centrewrite, the vehicle set up by the Corporation too close syndicates which were in run-off and on which Names were trapped indefinitely.) I knew the first quotation would be agony, the second would be easier, the third one would be easier than that because we were building a bottom-up database of old risks.”

As Deputy Chairman, Hiscox was active in cultivating and often seeking to correct the press. His impression was that Lloyd’s was badly treated by many newspapers and correspondents but “we had to keep talking to them.” He pulled them up whenever he could demonstrate an inaccuracy, spending most of his time on briefing the accurate journalists.

Webnote 22: Letter from Robert Hiscox, 7 July 1993 *

In July 1993, exasperated by many remarks about his having once referred to sheep being fleeced, Robert Hiscox wrote this:

‘A response to my sheep letter to John Rew

For 12 years I have kept quiet as John Rew has misquoted from a private letter that I wrote him in 1981. Now that selected excerpts from the letter have featured in two television programmes, the time has come to give the true facts.

The correspondence concerned the then newly produced League Tables of syndicate results. I was warning that Names would second-guess their agents and use the tables to chase syndicates which have made big profits but which could make big losses, instead of concentrating on picking a good agent. (I had no idea how horribly true this would turn out to be).

I wrote: “the most vital part of membership of Lloyd’s is the initial choice of agent and his choice of syndicates for the Names. Given that neither agent nor Name should wish to switch syndicates often, the initial portfolio is vital and this list [ie the League Tables] does not help choose a good syndicate. It relates to past performance which is often no measure of future performance. Prospective Names will be easily satisfied by being given syndicates out of the top section of the list and will probably demand syndicates from the top section when they may be better off with syndicates that have done badly but that have a bright future.

I have no sympathy for Names who regularly get lousy returns from their syndicates. They should be able to realise this fact without your list and should be adult enough to change agents if they are being permanently abused. As Eli Wallach said to Steve McQueen “if God had not meant them to be sheared, he would not have made them sheep.” And as Robert Hiscox says regularly to everyone “we must not legislate for the lowest common denominator.”

You will notice that I wrote that I had no sympathy for Names who made below average returns. Returns to me means profits. Of course I have total sympathy for any Name who loses money.

As John Rew has tried to damage my reputation, in legal tradition I believe that I am allowed to comment on his behaviour.

John Rew in fact asked our agency to be his members’ agent. This was hardly the action of a man who believed that we wished to “fleece” our Names (as he regularly misquotes.) We declined. He had always considered himself an expert on syndicate selection. We did not believe that his judgement would agree with ours and we did not want to risk a constant clash of opinions.

I am genuinely sorry that John chose Gooda Walker to be his agent and supported their syndicates and has lost money at Lloyds and I can understand his bitterness towards me and the society. However, I stand by my record as a members’ agent who has charged low fees and produced well above average results for his Names, and I believe that my flock would agree that I have been a caring Shepherd.’

Robert RS Hiscox

7th July 1993

Hiscox made the same point in a letter to the Economist in April 1994, saying that the review of Adam Raphael’s book on Lloyd’s “yet again regurgitates my ‘sheep to be sheared’ quote and perpetuates the misinterpretation of that part of a private letter I wrote 13 years ago.”

He said that “to infer that my foolish quote from a film 13 years ago is any indication of a lack of sympathy from the management at Lloyd’s either past or present is highly mischievous.”

Webnote 23: Initial Equitas project structure *

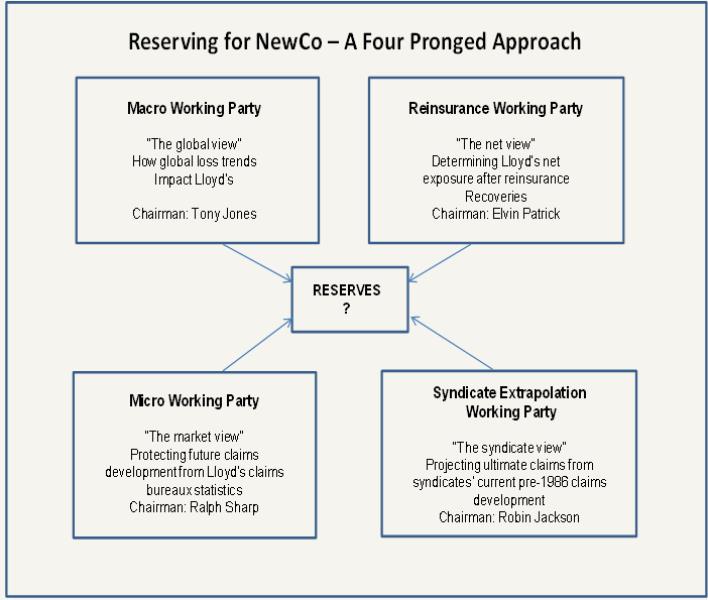

Four teams were created to work on different aspects of the project: the Micro team led by Ralph Sharp, managing director of Archer; a macro team led by Tony Jones; a syndicate extrapolation team led by Robin Jackson of Merrett who was steeped in the problem of old year liabilities; and a reinsurance team led by Elvin Patrick of Bankside, who had been a member of the task force.

This structure was the brainchild of Richard Keeling, who wanted the eventual result to be defensible against attacks from any direction. Each team would work towards determining the right level of reserves to cover all Lloyd’s liabilities up to 1985. Each confronted the issue from a different perspective, tapping different sources of information. The steering group would then draw together the numbers and the methodologies to determine a market-wide reserving strategy. The first three teams were each supported by different leading firms of consulting actuaries, Bacon and Woodrow for the Micro team, Tillinghast for the macro approach, and Coopers and Lybrand for syndicate extrapolation. The reinsurance team would attempt to assess the reliability of the reinsurance recoverables that each syndicate would be relying upon.

Webnote 24: Gooda Walker Action Group (GWAG) *

Case Preparation

The following material is drawn from GWAG Newsletters.

Deeny set out the rationale for choosing Wilde Sapte: they had no conflicts of interest, a large litigation department and relevant experience. He also described Jonathan Mance QC as one of the leading insurance silks in Britain with extensive experience of Lloyd’s. He had acted as junior in the Sasse case, and had cross-examined Derek Walker in another case. Deeny saw the loss review report as “a marvellous kick-off.” He also explained the importance of expert witnesses, and the difficulty of finding those willing to testify, because they did business with Lloyd’s.

He stressed the importance of the points of claim that would be made when the writ was issued. He also urged members to persuade others to join the cause, saying that the train was about to leave the station and they must buy their tickets now. The possibility of a settlement was no reason to delay. As he put it, “Any settlement offered will involve a substantial discount element. There is no doubt that we must have the resources to fight our case through the courts and the best possible legal team to do so. Equally, there is no doubt that we must move as rapidly as possible to commence and continue proceedings. There is nothing that produces a better offer of a settlement than the conviction on the part of the other side that they will lose if they go to court. To sit and wait for settlement proposals would be futile.” He wanted a legal fund up-front, saying “because many of our members may go into hardship or have to make arrangements with their creditors, it is better for them to pay the cost involved now. The knowledge that we have the funds to go through to the end will have a powerful impact on the other side.”

Deeny was elected vice chairman of the GWAG at the end of November 1992. Six weeks later he was elected Chairman, to take effect from March. Doll Steinberg had made proposals for the GWAG committee to be quite heavily incentivised. Soon after these had gone down badly with the membership, he resigned. Tom Benyon was one of several to recognise Deeny’s steeliness and sure sense of purpose, encouraging him to take over. Deeny’s newsletters continued to explain the course of events and the committee’s strategy. There were a non-stop series of issues confronting the action group which required very clear thinking and careful handling. One issue being played out in the courts was the interaction between recoveries made by Outhwaite Names and their personal stop loss insurers. Some of those Names had already claimed back part of their losses from their personal stop loss insurers. Now that they were due to receive their settlement proceeds of £116 million, the stop loss insurers wanted their money back! The matter went to court and eventually to the House of Lords – in those days, Britain’s equivalent to the Supreme Court – to be resolved. Their Lordships came up with a ‘top down’ formula whereby some of the proceeds had to be repaid.

Deeny and his legal advisers studied this issue carefully and tried to reach an agreement with the stop loss insurers in advance of the court hearing. Although a few matters were usefully clarified, it proved impossible to strike a deal. The basic problem for stop loss insurers, and for errors and omissions insurers too, was that they in turn needed to be able to recover under the terms of their own reinsurance policies, which were frequently with companies outside Lloyd’s. These reinsurers would be unwilling to pay in support of a deal unless they were convinced that it was on the leanest terms possible. They were only strictly obliged to pay for losses resulting from court orders. This provided a h3 incentive for the action group to go all the way to court and secure a clear judgment of negligence. This was explained clearly to the GWAG membership.

Deeny took an early view on the new leadership of David Rowland and Peter Middleton. He reported to his members on a meeting held shortly before Rowland had taken up his new position as Lloyd’s chairman. He said that Lloyd’s immunity from suit under English law was ‘virtually impregnable.’ Rowland had accepted, however, that there had to be a moral responsibility on the whole Lloyd’s establishment to try to rescue the victims of the spiral. Deeny believed that Middleton’s initiatives had followed Rowland’s direction. He told his members “he is clearly sincere in his determination to help the afflicted Names.”

In March 1993 proceedings were issued by the action group against Gooda and partners, Gooda Walker and 69 other members’ agents, alleging negligent underwriting. Deeny thanked all those involved in getting the proceedings issued on time, saying that members of the Wilde Sapte team had worked often seven days a week and sometimes until midnight. He was working very long hours himself.

The action group raised over £5 million to finance the litigation. The Names’ eagerness to participate was such that a second writ had to be issued in July 1993. The final number of Names on the writ was 3,095 – the largest number of plaintiffs on a writ in English legal history. In July 1993, the Gooda Walker action group was granted an expedited hearing of their case to take place in April 1994. Before this date a number of preliminary issues were heard in the High Court. The agents alleged that Names were contractually obliged to pay 100% of their losses before they could sue their agents. However in July 1993, Mr Justice Saville found for the Names. He ruled that Names who had not paid cash calls could sue their members and managing agents for breach of duty, despite the so-called ‘pay now, sue later’ clause in agency agreements. The judge said the object of such clauses was to ensure the uninterrupted collection and distribution of funds thought necessary by the agents, “But there was no good reason to shelter them from liability for failing to perform their duties.” This was subsequently supported on appeal.

The members’ agents also tried saying that they were not contractually responsible for any negligence by the management and underwriters of the syndicate they selected for Names prior to 1990 (when the contracts changed.) This preliminary issue was heard in October 1993, and also decided in favour of the Names. It then went to the Court of Appeal who confirmed the decision of the High Court. The agents then appealed to the House of Lords who also decided in favour of the Names in April 1994.

As preparations were under way for the main case, Geoffrey Vos, originally the ‘junior’ barrister, was made a QC at the age of 37. He was clearly highly rated. Although QCs are usually paid more, at first he kept his rates at the level at which he was first engaged. Jonathan Mance QC became a judge.

In early 1993, GWAG members were reminded that the Lloyd’s Names Associations Working Party tried to ensure that action groups worked together for the common good and profit from one another’s experience. The GWAG committee was then a h3 supporter of the LNAWP, and believed that it had a particularly valuable part to play in discussions with Lloyd’s senior management on the relief of distress among present Names and the ways by which the Society could achieve a profitable future. Tom Benyon was credited with influence in bringing the working party into existence. Deeny was a member and Raymond Nottage was the working party’s secretary. Nottage had also been elected as vice-chairman of GWAG. Readers may recall that it was Nottage who had challenged Miller at the 1984 AGM on the policy of rapid expansion of Lloyd’s membership. He had been put down.

Interviewed later by the author, Deeny explained his strategy: “Quite a lot of action group leaders were too impatient. They didn’t like suing the agents, because they saw it as a long lengthy process. They wanted to find some nuclear weapon that would blow up Lloyd’s overnight, or force Lloyd’s to compensate us. That was the debate that went on inside many action group committees, but ours was important because we were the biggest action group and we had the biggest losses. There was a separate point, which actually was more important to me: I never believed that Lloyd’s as an entity, either as a market or the Council of Lloyd’s, had deliberately set out to defraud the Names. I do think…that there was a pretty grave error of judgement and a failure of regulation in the over-expansion of the market in the 1980s. This had a bad effect on the rates and it led to the appointment of poor underwriters who should not have been allowed.” As is now widely acknowledged, Deeny thought that this over capacity in the market fuelled the LMX spiral – put simply the new syndicates insured each other.

“I think part of what drove the early action groups and drove the anger was the initial reaction of the Lloyd’s establishment to the big losses. To be frank, David Coleridge was the wrong chairman to deal with the problem. There was a good deal of old Etonian arrogance which was ill judged. There was a particularly disastrous interview in The Times. It was very unwise. With the coming of David Rowland as chairman and Peter Middleton, there was a difference in approach. The Names hadn’t to be honest a great deal of confidence in David then….. Because he had been on the Council himself previously and because he was chairman of a major Lloyd’s broker, he was perceived as a Lloyd’s insider. So his appointment didn’t change the atmosphere, although in reality it was obviously important, whereas I think Peter Middleton’s appointment did change the atmosphere.”

“I took the view that the appropriate strategy, the strategy which eventually other action groups followed, was that we wouldn’t try to bring Lloyd’s down or sue Lloyd’s centrally or attack it, but what we would do is vigorously sue our agents. But it was always a parallel strategy we would negotiate with Lloyd’s. We had to revise the committee a lot and get rid of the extreme anti-Lloyd’s element. We actually threw out a Member of Parliament, a man called Paul Marland. I just thought that we had to keep the dialogue with Lloyd’s going, and we always would have much rather had a settlement. Of course when you are negotiating you have to have a credible alternative, so litigation always had to be real, but we never expected it to go on as long as it did.”

In May 1993, the Randall report was published, commissioned by those by then responsible for running off the Gooda Walker syndicates. Deeny’s newsletter described it as a shocking indictment of the management of the Gooda Walker syndicates. It appeared that whenever the syndicates had a bad year, they simply went and purchased ‘time and distance policies’ so that their accounts would show a substantial profit. Syndicate 290 had substantial losses on its underwriting in 1981, 1983, 1985, and 1987. The published results regularly showed it, however, to be one of the most profitable syndicates at Lloyd’s. Many Names, impressed by these figures, were happy for their agents to place them on their syndicate. In consequence it experienced a massive growth from £5 million to £54 million in eight years.

The organisation now responsible for running off the syndicate had sent the Randall report to the Serious Fraud Office. Errors and omissions insurers had been suggesting that if fraud were found, it would invalidate all of the errors and omissions cover for the members’ agents that were being sued. The newsletter explained that in fact the errors and omissions policy for Gooda Walker itself explicitly covered fraud. Although they had not seen the members’ agents’ policies, it was unlikely that they would be invalidated. The newsletter sought to reassure members that the Randall report did not change things materially. The committee continued to believe that negligence would be much easier to prove than fraud, and that this would still bring realistic compensation.

The Randall report strengthened the case against the syndicate’s auditors, who had not objected to the treatment of the time and distance policies in the published accounts. It also raised the possibility of a breach of duty by the brokers who had placed these policies with a related company. The newsletter said that Lloyd’s had done nothing to regulate time and distance policies, which it described as “extremely dangerous financial instruments.” It further claimed that by refusing to allow the discounting of future claims, Lloyd’s had actively encouraged the use of these policies. In that matter “Lloyd’s stood condemned of an unacceptable regulatory failure.” It said that every pressure would be put on Lloyd’s to acknowledge their failure and offer a substantial financial contribution towards members’ losses.

In spring 1993, the chairman of the four leading spiral action groups met with the five leading E & O insurers – Stephen Merrett, Brian Smith, Don Carey, Alec Sharpe and Malcolm Cox. This was not a negotiation, but it did enable both sides to state their positions to one another. Deeny argued that there was no reason for them to withhold the details of the policies and schedules. They thought otherwise.

At one point, the GWAG committee reminded its members that in some circumstances applying to the Hardship Committee could be a better route. Any member in this position was told he could apply to withdraw from the proceedings. If there was evidence of real hardship, they had discretion to refund litigation subscriptions. Members were urged not to telephone the expensive city solicitors, Wilde Sapte, as this would incur costs that the AG could not afford. July brought news that Mr Justice Saville had granted an expedited hearing to begin on April 26, 1994. This was earlier than many had expected. In the same month, in an effort to reach a settlement of the disputes, Lloyd’s announced the formation of two panels: one legal, the other financial. The financial panel was established under the chairmanship of Sir Jeremy Morse. Deeny had agreed to serve on that panel saying that while it might prove onerous it should enable him to get a first-hand view of what contributors might be prepared to offer. It would also give him a chance to apply direct pressure on the size of any offer.

The legal disputes panel was appointed under the chairmanship of Sir Michael Kerr, PC. It comprised Stuart Boyd QC and Stephen Tomlinson QC. Their task was to advise on the strength of claims in legal disputes involving members of the Society, members’ agents, underwriting agents and auditors. The financial advisory panel would be led by Sir Jeremy Morse, former chairman of Lloyd’s Bank plc and would consider the financial contributions available and recommend a possible settlement offer. It would comprise David James, Neil Shaw, Christopher Stockwell, Michael Deeny and two errors and omissions underwriters: Don Carey and Brian Smith.

Deeny reported to his members on a lengthy meeting with the assistant director of the Serious Fraud Office. The SFO had now decided to launch a formal investigation. He believed that it was right to assist the SFO in bringing Derek Walker to justice. He also argued that such an investigation and prosecution – if that ensued – would help to reveal the substantial regulatory failure by Lloyd’s. This in turn would put pressure on Lloyd’s to make a larger contribution towards a settlement. In the meantime, Deeny had written to David Rowland and Peter Middleton asking them to suspend all cash calls and deposit draw-downs on Gooda Walker Names in view of this investigation. He said “it would be manifestly unjust for them to continue to pursue our members in these circumstances.”

On 31 July, the Court of Appeal decided in favour of the Gooda Walker and Feltrim action groups on the ‘pay now, sue later’ issue. They confirmed the judgment of Mr Justice Saville in the High Court. Their judgement was unanimous. Sir Thomas Bingham, the Master of the Rolls, said that the agents’ construction of their contracts would “work severe hardship to the Names without corresponding benefit to the market and would give rise to offensive anomalies.” Lord Justice Hoffmann said “the construction for which the agents contend means that if they are going to be negligent, they should rather ruin their Names entirely than leave them with enough resources to pay their calls.” The top of the judiciary appeared convinced about the Names’ case.

September brought Gooda Walker Names more good news. A number of members had applied for legal aid and been rejected. They were successful on appeal. However it was not feasible for any further applications to be made. At this point, the AG committee decided not to nominate for election anyone who was conflicted by pursuing individual actions, or those involving competing claims.

In October Mr Justice Saville found in favour of Gooda Walker and the Feltrim Names on the fundamental issue of the legal liability of members’ agents for the underwriting in 1988 and 1989. The Times described this as ‘an important High Court victory.’ The AG were also awarded costs in full, to be paid immediately. Deeny told his members that this finding was vital to all Names’ action groups that rely on these contracts. In their own case, the issue was the last major legal hurdle before the main hearing would begin in April. It was appealed, but the Names won that too in December.

Settlement Instead?

With several roadblocks removed, the route ahead was looking fairly promising. But now the GWAG Committee had to confront an alternative course. Lloyd’s efforts to put together a comprehensive offer to all litigants were about to materialise. In principle, this was Deeny’s preferred option.

His November newsletter prepared his members for the likelihood that Lloyd’s would make a settlement offer in the near future, and would tell them that it was the last and only chance of a settlement. He told them “not to be swayed by Peter Middleton’s passionate advocacy, but instead to engage in a purely factual evaluation of what an offer would mean for each of us financially.” He said it was important to look at the new regime’s deeds rather than their expressions of sympathy. Their deeds had been very disappointing. They had for example continued the policy of the previous regime in ‘imposing penal and positively usurious interest charges’ on the debt balances, and they had not lifted a finger on the issue of the massive foreign exchange losses, which could have been avoided by a letter of comfort from Lloyd’s to the bankers involved. They had also refused to delay the cash calls and deposit draw-downs despite the fact that the Gooda Walker syndicates were the only ones being investigated by the SFO. It was important to bear all this in mind.

Later in November, Deeny told his members that they were “now involved in a multi-level, multi-lateral process of negotiation of a most complex and demanding nature.” He feared an attempt by Lloyd’s to “bounce us into an agreement” and predicted a very determined campaign to convince everyone this was the only hope of a settlement. He urged the deepest scepticism. He told them not to sign any document before receiving the AG’s advice. He warned of the probably insuperable problem of a cap on future liabilities, saying that a Name with open years had always to be concerned with the possibility of future deterioration. He reminded members that those who had accepted settlements in the past had seen what seemed like a good deal at the time eroded by ever-increasing losses. He said that Middleton had indicated there would be a cap, but “we fear this may be another promise he may not be able to keep.”

At this stage, Deeny told his members “you may have seen press comment suggesting that the offer might amount to 30% of our losses. In our case this would come to £165 million. It would be wrong to describe such a large sum of money as insulting or absurd….. we believe it is substantially less than what the action group would recover through litigation, and we would not under any circumstances recommend acceptance at this level or anywhere near it.”

Deeny also said that another major issue in the negotiations was the repeatedly expressed desire of Lloyd’s ‘to treat all Names alike.’ On this he said “These are weasel words indeed. What sounds like equity actually involves paying away E&O insurance money and central fund money to people who are pursuing no legal claims and who, because of their stop loss insurance, may have suffered losses that in real terms are much less than ours. These people also include the Lloyd’s insiders who are not members of action groups. This aspect of the proposed settlement is another Lloyd’s insiders’ deal.”

Finally, Deeny turned to the fear expressed by some members that there might be a partial settlement which would reduce the amount of errors and omissions cover left to pay GWAG claims. He thought this unlikely, for several reasons. First it was more likely that the AG’s would stick together and that if it was unacceptable to GWAG, it would be unacceptable to most others too. The second, because of their size, a settlement without GWAG would be no real settlement at all. Third it would bring 20 Lloyd’s members’ agencies much closer to liquidation.

He ended this review as follows: “I will now conclude by stating that we on the committee are always extremely conscious of the anguish and suffering that has been caused to many members of this action group over the last two long, bitter years. We are very aware that many Names regarded their investment in Lloyd’s as a source of extra income to bring some comfort to their retirement. We are particularly conscious of those elderly and retired people, many of them had worked long and hard to create the capital that enabled them to join Lloyd’s, who have seen the latter days of their lives overshadowed by the fear of financial ruin. We appreciate that on the one hand a settlement and an end to anxiety and fear is very desirable for all of us. On the other hand, an inadequate offer that is massively less than what we might gain in court will not solve the problems that many of us face.”

“For the reasons set out above, the committee of GWAG continues to be pessimistic about the possibilities of any reasonable agreement negotiated. However we feel it is our duty to attempt to extract the best possible offer from Lloyd’s. If it is unacceptable, then we will be clear in our minds that we have no alternative to resolving these matters in court. In the meantime we will continue vigorously to pursue our litigation, which in any event we believe is the most effective method of putting pressure on the other parties involved to arrive at an acceptable settlement.” This letter was followed a week later by one reporting a fresh glimmer of hope, as several concessions had been won. However the odds continued to be against an acceptable offer being made.

The book records the subsequent decision to reject the first settlement offer, the continued litigation and its outcome. It also records the subsequent twists and turns as Names attempted to secure their winnings.

Webnote 25: Lloyd’s First Settlement Offer, December 1993 *

The settlement offer aimed to compensate 21,000 members on a total of 67 underwriting years for losses which could, in part, be judged to be due to misconduct or negligence by agents. A total of £900 million was offered to those affected, which was made up of contributions from Lloyd’s centrally, the agents involved and the errors and omissions underwriters who wrote the cover for the agents affected. Speaking at its launch, Rowland said he believed it was for the general good of the whole community, but each member must look very carefully at his own circumstances. Rowland explained that the offer would redistribute some of the assets of the Society in the interests of the whole community and in the interest of fairness. Borrowing was not thought desirable since it would create liabilities would have to be repaid. A Helpline, manned by specially trained Corporation staff, was set up to answer members’ queries on the settlement document; by the end of December it received over 1,400 calls.

David James, an external member of the Council, with a reputation as a ‘company doctor’, served on the financial panel as its deputy chairman. His advice on whether this offer was worth accepting would be taken seriously by many Names. The January 1994 edition of OLS contained his personal advice – acceptance – and the views of James Birkin, another external member, advocating rejection.

James stressed the uncertainties involved in further litigation. The limited amount of E&O cover available fell far short of the total claims. If the first action groups were successful, there would be very little left for subsequent litigants. Lloyd’s had augmented the E&O offer to produce a total of £900 million. The settlement was weighted towards the action groups who were furthest ahead in the courts – Gooda Walker and Feltrim. Lloyd’s could not produce a better one if the offer was rejected. Litigation would simply take its course without a central contribution. The offer made cash or credit available immediately and would avoid years of uncertainty and litigation costs. He thought it should be accepted.

Birkin stressed the absence of a cap on each Names losses. If they continued to escalate, and if the cost of Newco were to prove high, the offer might be seen as inadequate. The chance to force Lloyd’s to reconsider capping losses would be surrendered. As he put it, “In accepting the offer, the Name gives an open cheque-book to Lloyd’s and becomes a hostage to fortune.” It meant abandoning a vital protection against agents and Lloyd’s in return for sums which were insubstantial even in relation to the known losses. Accepting this offer seemed “unwise in the extreme.”

Among the letters in this same edition was one from an external member who had served on the Council in the early 1980s. He said that the decision was difficult because “We are all so incensed at the way things have gone that many of us feel that if ‘I’m going down, I’m going to take Lloyd’s with me.’ When all the anger wells up, like others, I often feel it would not be a bad idea if Lloyd’s did disappear. However it is not comfortable to go through life being permanently furious. In my calmer moments, reason dictates that it would be very unwise for Lloyd’s to disappear in a cascade of lawsuits over many years – the only people who get rich that way are lawyers. So, however angry we are individually, we need to try to disentangle ourselves and realise that the only way to a better future is to accept the settlement and to get on with our lives as best we can, but at least a bit more peacefully. The alternative will be the stony road of endless litigation which will drag on for such a time that many others will be permanently embittered to Lloyd’s and that bitterness will spill over into the rest of our lives.” He ended by saying “let us release ourselves from our anger and accept the settlement. Being broke and human is better than being broke and bitter.”

The ALM welcomed the fact that an offer was made, but expressed disappointment that there was no ‘cap’ on future losses. Charles Sturge of Chatset was still concerned about deterioration on old years, but felt that members on LMX syndicates should accept the offer. He congratulated the two panels and Lloyd’s on what he described as “a Herculean task of coming up with a settlement offer.” Christopher Stockwell of the LNAWP said the offer was “an exercise with mirrors to reduce Names’ theoretical indebtedness to Lloyd’s. Most Names will receive nothing except a nominal allowance towards next year’s losses.” The closing date for acceptance was extended to 14 February, in the light of some errors that were discovered after the offer was sent out.